Publication and the People

“This approach enables a workflow where interpretive decisions can be delayed to a later phase of the project because the material uncovered by the excavation and the record produced by the individual excavator is seen as impartial and atheoretical.” 1

I don’t think I’ve ever analyzed a topic model made from a larger dataset than this before and I have to say, while it’s incredibly informative and great for putting such a significant corpus into perspective, it’s also pretty fun to click around and explore to understand the mechanism behind it. For example, Topic 39 is just a grouping of German words. This is likely because most of the journals downloaded were in English, and so phonetically it makes sense that these words were matched then made a singular topic, but it’s nice to know that the program used to create these topic models knows just about as much about what the German word actually means as I do.

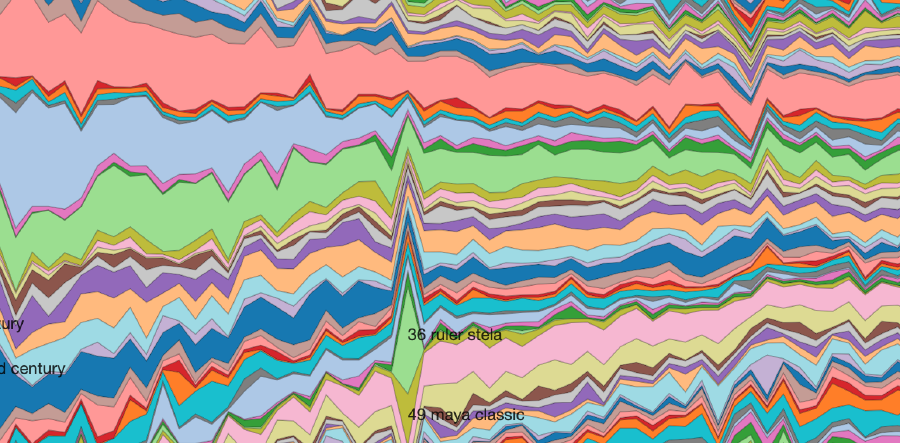

But beyond the humour, the other element I like about topic modelling is how it makes you think about the meaning behind the topics created in ways you might have never thought of them, especially once visualized. Maybe it’s because I liked the colour or maybe because it was in the middle of the graph, but once I saw the stream graph of this topic model that spanned 75 years of archaeological scholarship the first thing I was drawn to was the spike in Topic 36 (ruler/stela/tikal/date). I knew that Tikal was an ancient Mayan city (and was shocked that I remembered that fact from my grade 11 history class), but what happened in ~1976 that made it so “popular” among archaeologists? Upon some googling, I learned that apparently, the University of Pennsylvania hosted the “Tikal Project” which performed extensive excavations of the site from the 1950s until 1970. Some of the articles seem to reference the structure of this cityscape, so I assume that these publications in 1976 are a result of that project. Immediately, the course note that prefaced this analysis came to mind:

(Remember there’s a lag between work being done, and work being published).

Based on my observation, if it’s correct, this means there was a 6 year delay between the project ending and publications relating to it being put out into the archaeological world. This made me think, how was archaeology EVER “current” in the past when excavations such as the Tikal Project only had publications released on them years later? I feel like this is just a testament to the necessity of collaboration in within archaeology, especially with the digital tools we have access to today. In the past, archaeology relied on “academic” formats such as journals to disseminate information to their peers– based on what little I know, this seems to have been the only respected way to do so– which came at the expense of a delay in receiving up-to-date information. Now? Sharing information is as easy as tweeting about a blog post someone wrote at the end of Day 1 working on site. Especially within the field of digital history and archaeology, I’ve noticed somewhat of a “deformalization” of The Academia, and I personally think this is excellent, because although archaeology is still considered by many to be an “academic” subject, how can we know about what’s happening in the field if we solely relied on traditionally academic mediums and publications that will only inform us of something happening years after a project is over? Further, why restrict these topics to the elite group of “academics” rather than sharing these projects with the community they take place in? We now recognize the importance of an informed and participatory community to prevent injustices such as this from repeating themselves (although should the field of archaeology not grow in its diversity as discussed in the White and Draycott article, things such as this are bound to happen again). But beyond just ethics, as Wilkins states in her article related to collaborative peer-to-peer systems for archaeology such as DigVenture, involving the community to actively collaborate via participation in the discovery process not only encourages civic engagement, it allows for new approaches and thoughts to be applied to the archaeological process and interpretation of its findings that may transcend the disciplinary boundaries that a trained archaeologist might unintentionally confine their process to. On a wider scale, this is one of the more significant benefits I see with digital archaeology– accessibility to participation in the archaeological process. Even if someone can’t be physically present on-site, through technologies such as video walkthroughs or more “advanced” technology such as AR, they can still participate in the process of observation, of exploration, and of accounting for ethics that need to be upheld.

Now, you may have noticed that while I’ve talked about digital participation, I haven’t referred to digital archaeology exclusively yet, and this relates to a point I’ve been thinking about the past couple of weeks that was brought up in the Perry and Taylor article– in modern-day, digital archaeology just seems like the future of archaeology as a discipline, despite currently being considered separate. Maybe it’s because of this class that I think this, but from what I’ve studied related to the field of archaeology broadly, in this day and age what archaeologist DOESN’T use digital tools? I can’t imagine not at least digitally mapping out a site to have coordinates or recording daily findings in some form of database. While they may not use these things to critically analyze their findings, they ARE fundamentally employing digital methods; thus, much of current archaeological theorisation should be based on that which digital humanist discuss– what these new technologies imply for the field they’re being used in. The trend I noticed in the topic models at least contributes positively to this– as the 2000s came to be, so did an increasing number of papers regarding the ethics of technology as used in archaeology. Additionally, the use of social media platforms is ever-growing and even those who aren’t involved in archaeology professionally in any capacity can and DO share aspects of it they find interesting about it. And of course, there are courses like the one I’m writing this for that teach potential future digital archaeologists within the framework of “slow archaeology”, where a large part of our process is to stop and think about what we’re doing. Although it’s said that digital archaeology lacks a larger critical disciplinary framework to guide our digital practice, if future scholars are taught to think deeply yet creatively about their work as a part of the process instead of after or not at all, then the framework that’s being given time to develop will likely be better than the on that much of traditional archaeology presently adheres to.

1 Wilkins, Brendan. Designing a Collaborative Peer-to-peer System for Archaeology: The DigVentures Platform. JCAA 2020. Designing a Collaborative Peer-to-peer System for Archaeology: The DigVentures Platform. Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology, 3.1, 33–50.

Photo a screenshot of stream line graph as seen here.