Technical Difficulties in Doing and Thought

“I worry that in our preoccupation with a paperless life we might overlook the legacy of paper and a closer connection.” 1

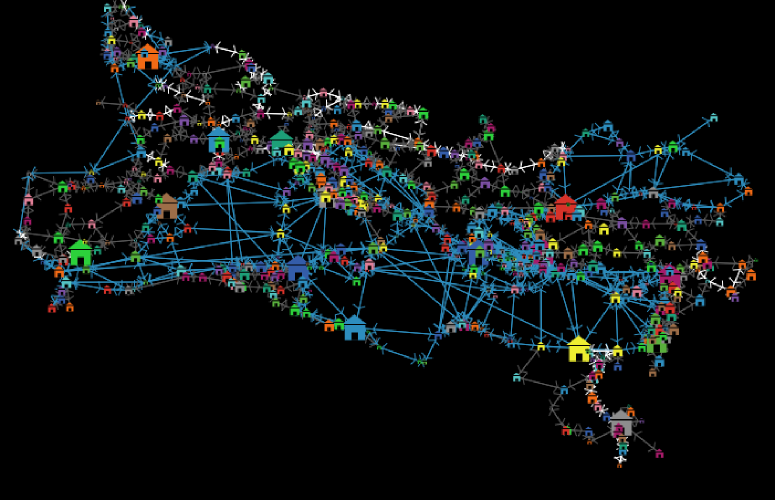

As someone who has been interested in figuring out how modern technologies and related methodologies could be applied to the study of humanities even before knowing about the existence of digital humanities, it’s safe to say that I certainly have an overall positive imagining on how the “future archaeologies” we explored this week can impact the field. I feel that these new perspectives generated by something beyond the human mind can lead to entirely different ways of viewing topics that otherwise would have never been thought of; tools such as Netlogo or GPT-2 can connect concepts that otherwise may have never made it past some form of hand-drawn diagram or a set of notes on a text, and allows them to be interacted with in a way that may alter what we believed to be fact.

But my god, if Netlogo had been the first tool I ever used when attempting to dive into the field of digital humanities, I would have jumped right back out of those waters leaving the rest of that ocean unexplored.

I don’t recall ever leaving an activity I started for class unfinished, but I met my match when it came to using Netlogo. The activity itself was in theory, not incredibly complicated. I understand the premise of ABM, it’s yet another concept that aligns with my education in HCI on mental models. The hypothesis Brughmans proposed for the activity was not exceedingly complex and I understood what was happening and what to look for as I read through the tutorial– my problem was actually using Netlogo. I’m very passionate about making technologies and tools user friendly, but Netlogo I feel tries to be so user friendly that it becomes tedious and frustrating to use. At least, it was to me, anyway. This might stem from the fact that I have a background in computer science, but in my mind and in the workflows I’ve come across– even those that I found similar to how Netlogo functions such as Visual Basic– you write the code and the code is what produces your results, which includes everything found on the GUI. Netlogo breaks this paradigm, where you write the code but then the code becomes secondary to the interface, where you’re seemingly required to manually add the element you want, define how it functions in a pop-up window, and link it to the related “procedure” that you wrote code for; one process is split between 2 different places. This disconnect led me to constantly making small errors as I switched back and forth between the sections, and the frustration that this was causing me is what ultimately led to me heeding the advice attached to each week of this course telling us to take a break when our digital work isn’t coming together and go back to it later. So I’ll get back to Netlogo later. Maybe.

I had a much better time with GPT-2 where, while there was no visual or click-and-drag component, there was a clear description of each line or small block of code, and thus simLanciani was created with ease. I didn’t have a lot of time to explore, but this activity was both fun yet also led to me imagining some eery possibilities. I initially gave simLanciani prompts that could be relevant to his work, the first simply being the word “ritual” and then asked the question, “What ties does the cemetery have to the spiritual?” Following this, I concluded my short text-cavation with simLanciani by asking him if he feels that I’ll ever be able to afford a house in today’s economy, curious to know his hot take on the 2020 economic climate, which resulted in me being perceived by a farmer concerned about my land. While this last response seemed rather comedic, just as the previous results were at times, they still made sense. What simLanciani was producing was not complete nonsense– when I was going over the output, what he was “saying” was akin to something like someone being asked a question they don’t know the answer to but they don’t want to admit defeat so they decide to try and answer anyway. In fact, I imagine if someone had no idea who Lanciani is, they might actually believe the responses from simLanciani are legitimate, and this has somewhat scary implications.

I can think of funny ways that a technology such as GPT-2 could be applied– I’m very tempted to try and train it by giving it a .txt file of all my blog posts, and then make it write a reflection by setting the prefix to one of the weekly prompts just to see how it’d fair. But how convincingly it can replicate the works of real people to the untrained ear speaks to, say, how easily false information could be spread due to someone missing that a work was generated rather than composed, sort of like deepfakes specific to bodies of knowledge. I think it’s realizations like this that are unsettling and thus contribute to the formation of an inherent weariness surrounding technology which becomes a piece of the larger reasoning that people feel reluctant to step into this world of “future archaeology.”

This week’s readings and activities coupled with having to reflect on the entirety of my education in relation to digital humanities while writing personal statements made me really think about how these tools came to be used, and how that can go hand-in-hand with the lenses of understanding they create. As I observed with GPT-2 and as Morgan delves deeper into in her article on cyborg archaeology, although they can be excellent tools for analysis and teaching archaeological methods, these technologies can also often blur the lines between fact and fiction. Further, there is also the risk that every article we read addressed this week, which is the trap of becoming engrossed in the digital and, by relying on it, important archaeological findings may be glossed over and ethics left unconsidered. While I felt her article tended to illustrate extremes about digital archaeology, Kersel’s article greatly illustrated the risks of making fieldwork a heavily digitized practice. There is not only risks of technology failing, but a loss of the “human” element of archaeology. “I often run my hands over features as I set up tapes” and “I worry that in our preoccupation with a paperless life we might overlook the legacy of paper and a closer connection” are just two of the instances in which Kersel debates how the distancing the archaeologist from their work may result also in a distance from their ability to find and interpret meaningful details. Situated between a stereotype of the digital archaeologist who forgets the humanity in their work, and Kersel, who fears this occurrence as technology becomes increasingly included in the wider practice of archaeology, is a medium that must be sought out where digital tools and methodologies can be used for the macroscopic lense they provide, alongside the more microscopic lense that humans tend to have which can not only be used for analysis, but also to recognize the limitations and consider the ethical implications of these technologies, and thus perhaps even see the sliver of humanity they contain, given to them by through the biases of their creators.

1 Kersel, Morag. 2016. ‘Living a Semi-digital Kinda Life’ in Erin Walcek Averett, Jody Michael Gordon, and Derek B. Counts (eds) Mobilizing the Past for a Digital Future: The Potential of Digital Archaeology. Grand Forks: The Digital Press at the University of North Dakota. pp. 475-492.