Reflections on Archaeology by Not-An-Archaeologist

“Learning the past through doing means engaging one’s body and heart, as well as mind in the process.” 1

I’m not an archaeologist; in fact, during the entirety of my history degree, this class is the first I’ve taken that has even had “archaeology” in the title. So, maybe the fact that I’m not an archaeologist and that I haven’t been trained in the processual traditions that still hold their place in the field are the reasons why I find the concept of NOT doing archaeology “from the heart” so unfathomable. This week’s article by Hodgetts and Kelvin discussing the heart-centred approach they learned through their work with the Inuvialuit community of Sachs Harbour was perhaps one of the most eye-opening works I’ve read this semester because it connected concepts that we’ve been learning about in this course regarding the historical practice of archaeology, how this continues to influence modern archaeological practices, and the implications that this has for the development of public and digital archaeology.

While I ultimately made the choice to study history, archaeology and its ties with historical representation played a significant role in shaping my interest in the humanities. Some of my fondest childhood memories are built around this, such as field trips with my class to the Cumberland Heritage Village Museum where we’d attend class in the one-room schoolhouse doing activities on slates from the 1930s, then later in the day learn to make butter in a restored butter churn. While interacting with these artefacts and being given the opportunity to use them instead of just seeing them in pictures or inside glass boxes, I recall a feeling of wonder, thinking things like “wow, there was a kid just like me sitting at this desk all those years ago, their hands held this slate just like I am.” These moments of wonder and feelings of connection are fundamentally what spurs my love of history and studying the past, and the purpose that studying it serves for me is that I can help create these feelings for others, using my knowledge to serve communities by connecting them with and teaching them about their pasts. Hodgetts recollection of the scientific and intellectual mindset she approached her archaeological work with– placing “the mind” over “the heart”– surprised me, because up until this reading I somehow have maintained the belief that the people who enter fields such as archaeology or history all do so for reasons similar to mine. I mean, why else would you go into these fields? I don’t think there are many in it for the money or fame they’ll gain. So if through your work you aren’t producing results that serve to enhance the understandings and connection for past and living people within the community you studying and even beyond them, what is the purpose of it? How is it meaningful beyond just a set of data points?

In relation to the Hodgetts and Kelvin article, I found myself reflecting on the digital work I’ve done this semester with archaeology, and found that my practice was quite heart-centred, even if I didn’t realize it then. Looking back at my earlier posts from when I was out working on-site at the Pinhey’s Point cemetery, I was constantly concerned with how my work might be received by or affecting a community I couldn’t actually communicate with, so I focused my efforts on communicating with their living relatives. I learned the history of the cemetery and those buried in it not just from “official” sources such as city records and documents, but from the grave keeper and her husband whose family had been buried in that cemetery for generations and passed down family stories not recorded elsewhere. Additionally, I ended up attempting to actually help the community as a thank-you by using my connections in the heritage sector to help find them a heritage stonemason able to repair a number of the 19th-century headstones that were cracking from weathering and age. Thanks to the pandemic this never worked out, but it did allow me to stay connected to the community I was working with and consider them in all of my actions, on-site and off. I reconciled my initial concerns with mortuary archaeology by doing as much as possible to respect and help the actual site of my work, while also ensuring I documented every headstone to the best of my ability, attempting to frame my work as a form of digital preservation which ensures that the memories of those buried there live on instead of simply becoming data points.

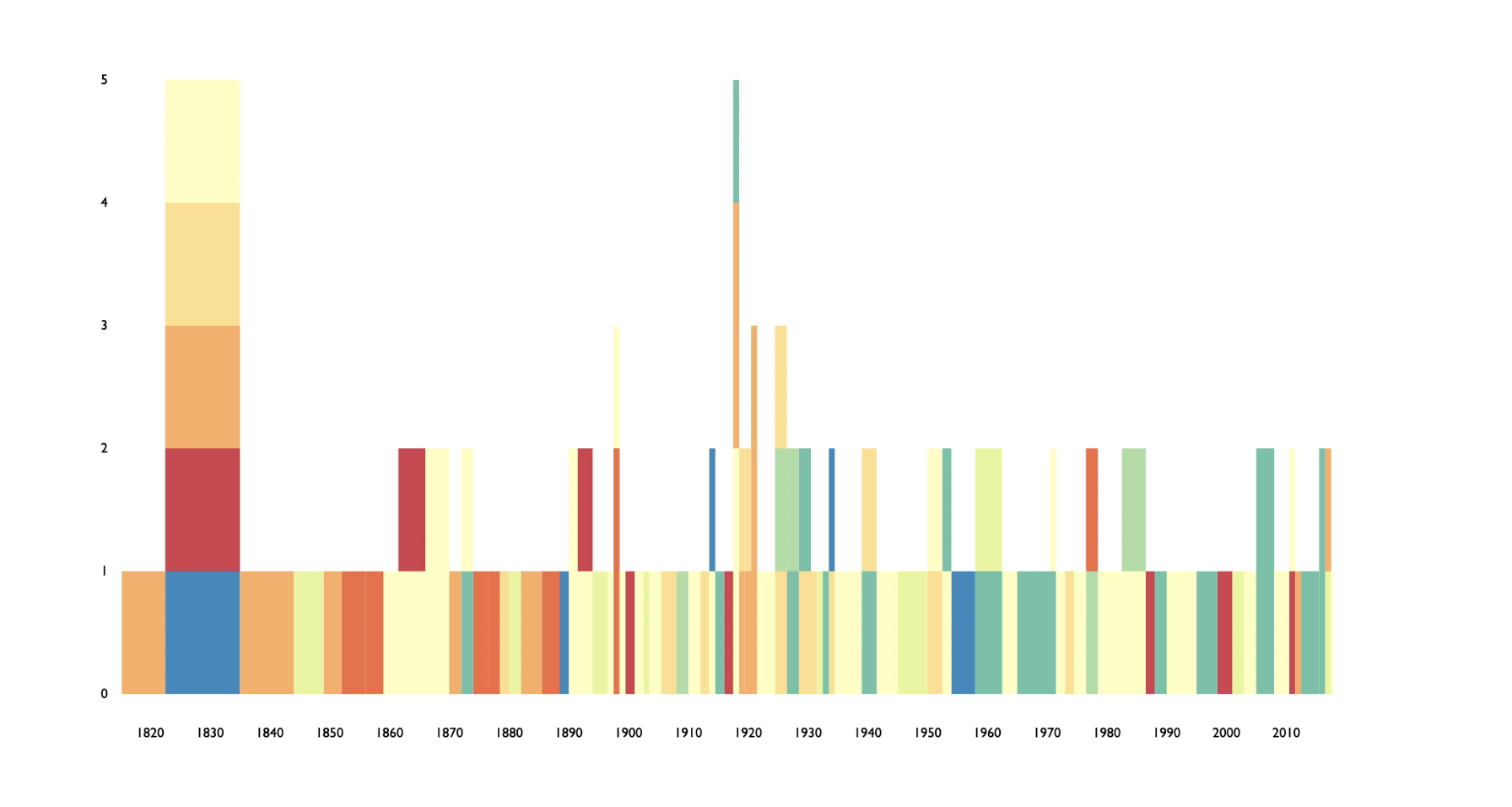

This sentiment was even somewhat a part of the struggles I faced when doing the Graveyard Compendium activity– aside from technology behaving strangely, of course. Before beginning my work, I thought HARD about the best possible way I could visualize the data without losing the person(s) present at each grave, and struggled with the fact that the dataset we were given didn’t include the information from the other form we filled out, which actually had the names and information on the people associated with each headstone. Ultimately, I decided to attempt to use the data to analyze changing funerary aesthetics from the 19th to 20th century in order to avoid factors that may reference these presently unknown individuals and had some… unsuccessful results…

I was struggling to find the best way to visualize the data, and settled on a stream graph to show proportional change of each style of monument type over time, but unfortunately, because the dataset was “only” 152 entries, there was rarely more than one type referenced for any given year. While I may have failed this week at producing meaningful work from the data my class and I collected, I will make every effort to continue to try and create something more from it because I feel that because I was given permission to use this data, I must create the best work I possibly can from it not only as a thank-you but as a sign of respect to the communities who helped us produce it. As I’ve learned throughout this course, when doing digital archaeology it is important to not only consider the impact your work in relation to the data gathered, but also the impact it has on the community that it is built from.

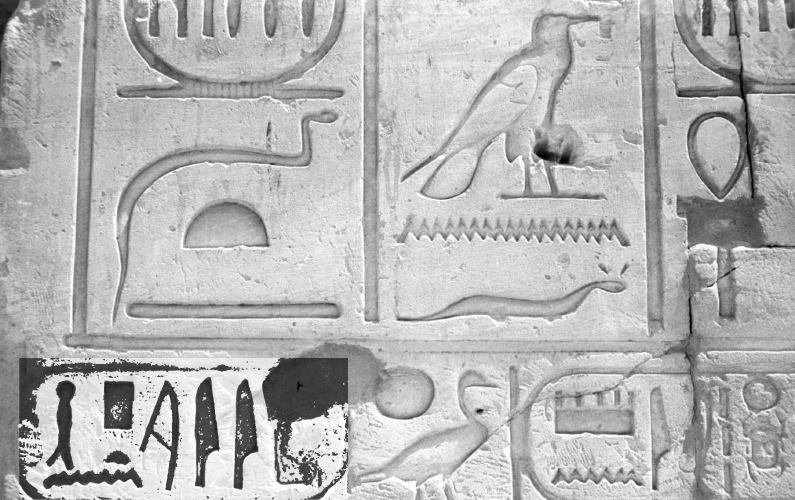

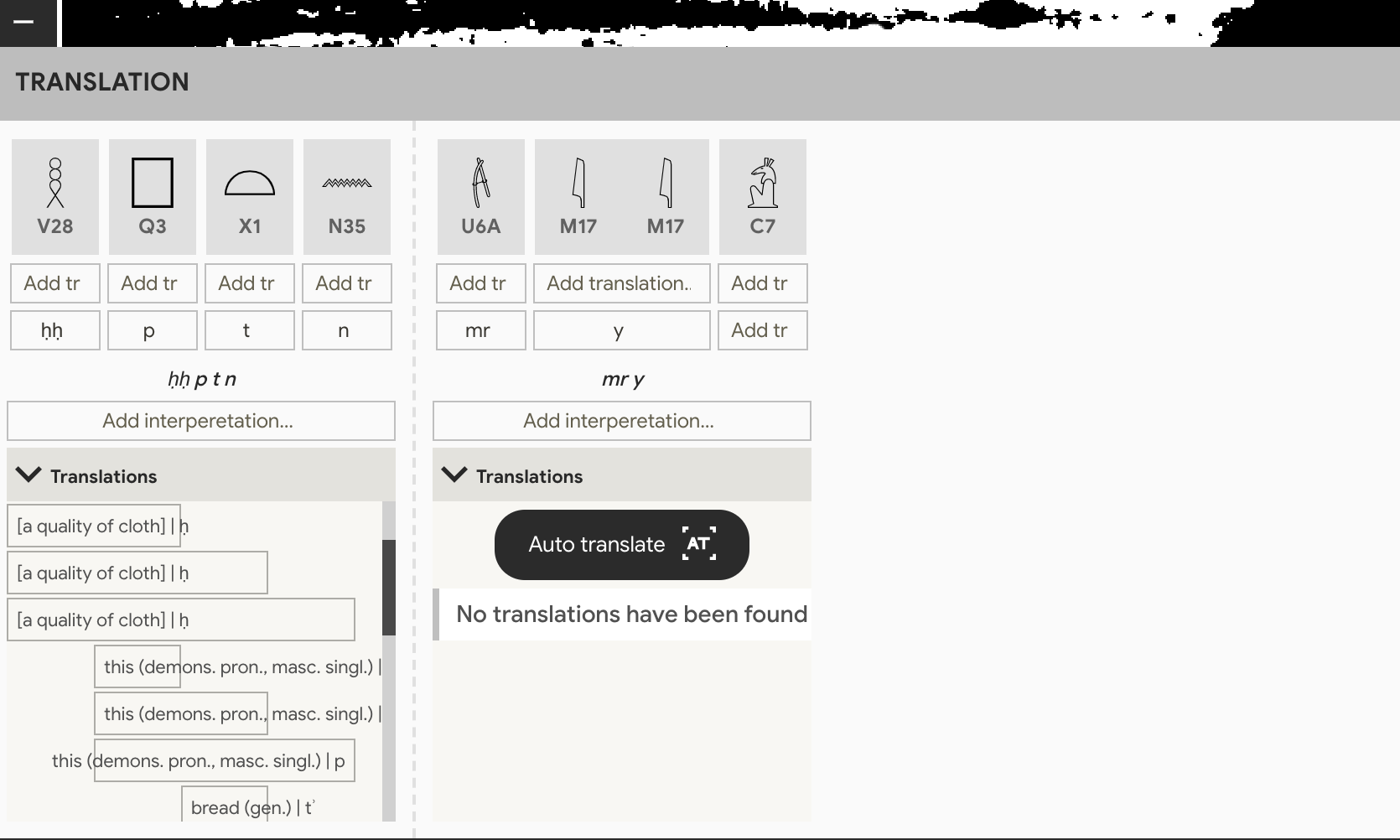

This same mindset is what I approached the Fabricius Workbench activity– asking myself questions such as what purpose does this tool serve? How does it contribute and integrate the communities it was designed for? According to the GitHub repository for the project, it is meant to be “the first digital tool that gives experts a fast way to decode the ancient Egyptian language (Hieroglyphs) and everyone else an easy way to learn about and even write in this ancient language.” Despite this intention, I certainly didn’t have an uncomplicated time using this workbench. The tutorial made it seem easy enough to use with its simplistic analysis tools and boasts about their machine learning model which supposedly could identify hieroglyphics on the “on the first go,” although “sometimes you need to select the second or third prediction.” The tutorial reassured my beliefs that this would be a fun learning experience where I could dust off my very dusty knowledge about hieroglyphics– as in, the last time I worked with hieroglyphics was doing an activity translating simple phrases at a museum exhibit about Ancient Egypt in grade 8. I selected this photo from a collection at the Smithsonian, and made it through the processing and generating stages with few problems– the problems I did face were mostly caused by me being a first time user of the tool– but the analysis stage quickly brought this ease to a halt. I cleaned the image to its outline, using Sidecar to trace the hieroglyphics as accurately as possible with my stylus, yet not once did the Fabricius Workbench correctly identify the hieroglyphic on its first attempt, and the additional predictions only offered correct suggestions twice. When it then came time to translate, the tool’s auto-translation function only worked for part of my work, and I couldn’t even really use it for the part that was translated because the translation results were almost unreadable, trailing outside of their boxes and even cut off with no option to resize that section to prevent this.

“Oh well,” I thought to myself, assuming they would feature a manual guide to hieroglyphics should their auto-translation fail. I then discovered they didn’t after scouring the Fabricius Workbench itself and rewatching? rereading? the tutorial over multiple times. Unfortunately, because I was now determined to figure out the name of the royal I was looking for I spent the next 2 hours reading a paper and learning all I could about the grammar and meaning of hieroglyphs. I’ll admit, I had a bit of fun… BUT it was still frustrating to me as a user when their technology did not work as advertised, and no alternative, manual or otherwise, was given as a back up to account for the possibility that their technology could fail. About 2 days after doing this activity, I discovered the project’s actual “home” which states that the workbench IS actually for those with experience translating hieroglyphics, but that the two other teaching activities their home page offered would give one enough information to use it upon completion. Yet when I worked through these activities to see if they could have been the solution to my translation troubles, I still found that there was a focus on showcasing the technology behind the project rather than explaining how to actually read and translate hieroglyphics as suggested. In each of the “hands-on” segments of the activity, the “info” button explains how the tool works rather than giving additional explanation or resources that relate to the activity as I expected it would, and throughout the entire tutorial, they only explain the actual translation of 3 out of the 9 hieroglyphs shown yet at the end of the tutorial you are asked to translate a phrase with no resources beyond your knowledge about the directional way hieroglyphics are read and the meaning of the 3 aforementioned glyphs. Much of this experience made me recall the article I discussed last week by D’Ignazio and Klein, where the problem of digital projects wildly overstating the completeness and accuracy of their data and algorithms is discussed. Both the tutorial for the workbench itself and even the parts of this project meant to be teaching unrelated to the workbench heavily emphasize the convenience and “coolness factor” of this tool’s features– features that did not work as promised for me, nor resulted in much learning. As I conclude this post, I can’t help but wonder, who was this tool really made for? Although implied to be a community-focused digital tool, I can only see experts who already have knowledge of hieroglyphics being able to truly use it, as they could translate glyphs even when the computer can’t. Further, is this tool available in Arabic so that those apart of the Egyptian community who desire to learn about their own cultural history can participate easily? I genuinely feel that if recreated with a true community focus rather than a more technological one, the Fabricius Workbench could be an amazing tool, allowing aspiring Egyptologists and those within the Egyptian community to connect with their past, and becoming an even better tool for experts because, by making the workbench more accessible to all, the AI improves through gaining more users who train it through their usage.

1 Hodgetts, Lisa and Laura Kelvin Z. 2020. At the Heart of the Ikaahuk Archaeology Project. In Kisha Supernant, Jane Eva Baxter, Natasha Lyons, Sonya Atalay (eds). Archaeologies of the Heart, Springer, Cham, 2020.